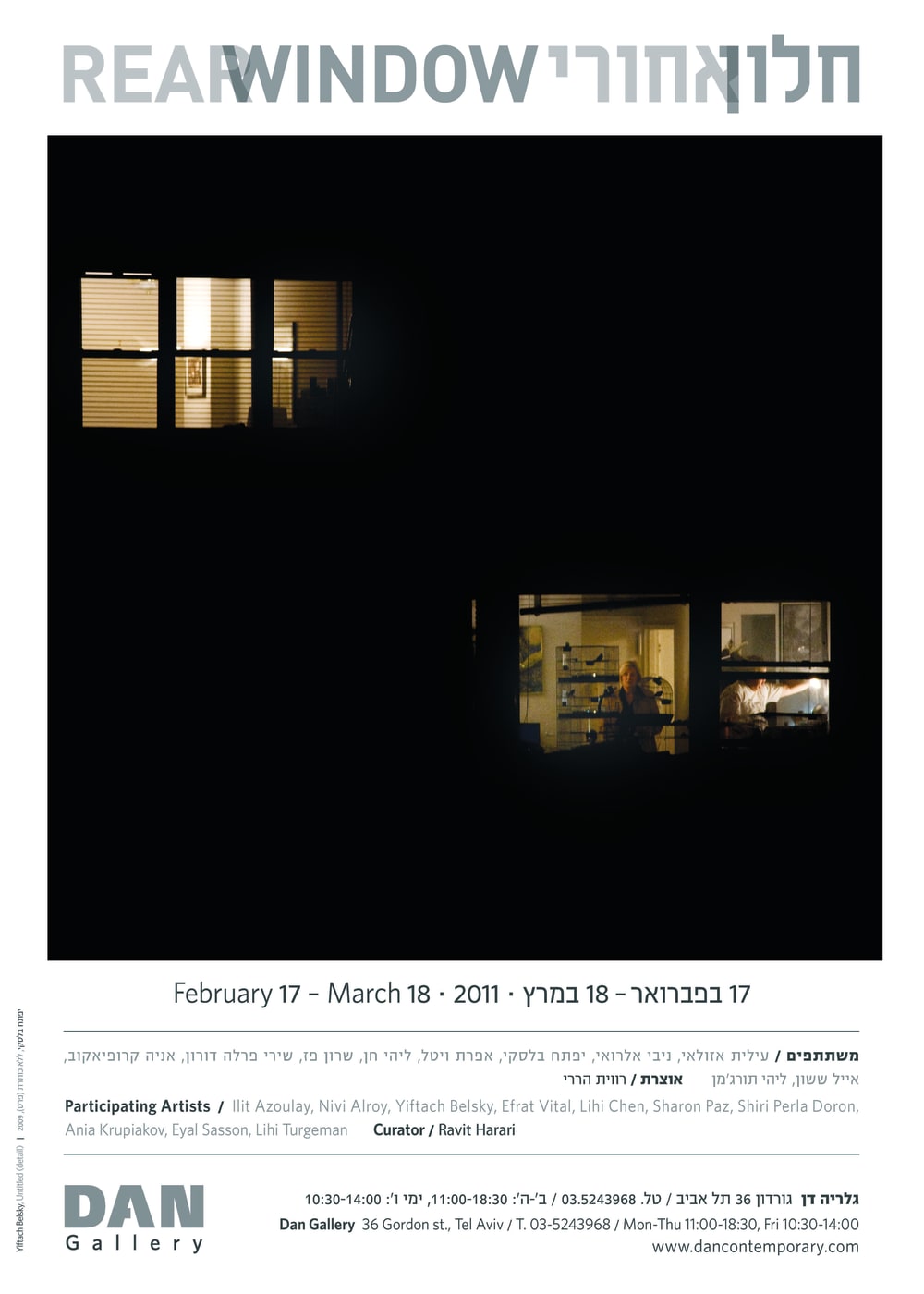

Rear Window | חלון אחורי 17/02/2011 - 18/03/2011

8 Participating Artists:

Lihi Turgeman / Lihi Chen / Yiftach Belsky / Efrat Vital / Eyal Sasson / Ilit Azoulay / Shiri Doron / Sharon Paz / NIvi Alroy / Ania Krupiakov

In the exhibition Rear Window the works center on various types of openings and thresholds, and on the range of meanings and voyeuristic opportunities to which they give rise. An opening functions as a border station of sorts, marking the line that runs between two different countries: interior and exterior, darkness and light, the visible and the invisible. It is no wonder, then, that this term has been the subject of numerous discussions in the fields of psychology, philosophy, and art history. In an essay on the work of Yitzhak Livneh (Studio 73), Dan Daor describes the hole in a gnarled tree trunk in one of Livneh's paintings as such an opening: "This combination of presence and absence, the 'hole and its lips,' is a highly charged icon. There is no wonder, then, that so many words may be used to describe its wealth of meanings: opening, crack, crevice, aperture, slit, fissure, wicket, window, depression, pit, pier, tunnel…" Daor adds that this hole is "a passageway between different spaces, or worlds… between brightness and darkness." Referring to Livneh's paintings, Daor also touches upon the sexual and spiritual aspects of the hole, and upon its representation of (repressed) sexuality and its role as a conduit for "introducing into the room a mystical form of light, so that the spirit of God hovers over the house." Holes and openings also play a significant role in Freud's theory of human development: according to Freud, every bodily orifice – anal, phallic or genital – comes to prominence during a specific developmental stage, so that the developmental journey may be described as a journey from one orifice to another. In psychoanalytic theory, openings are also symbols of the transition from the conscious to the unconscious realm, from what is explicitly known to what lies below the surface.

In the visual arts and in cinema, meanwhile, openings are often related to a desiring gaze and to voyeuristic fantasies, as is the case in Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window – in which the suspense arises from the voyeuristic behavior shared by the film's protagonists and viewers. In an essay on the significance of holes in the history of art (Studio 81), Itamar Levi argues that "The moment painting began concerning itself with the illusion of depth, it was transformed into a hole," into which the viewer peers. In this context, Levi discusses the perspectival holes created by Renaissance artists such as Brunelleschi, Piero Della Francesca, Masaccio, Alberti, Donatello, and Uccello. He pays a special attention to Andrea Mantegna's ceiling fresco in the Camera degli Sposi (The Wedding Chamber) in Mantua's Ducal Palace (1474), where the hole becomes "a most explicit reference." As Levi concludes, "Perspectival thought aims to extend beyond itself, to the hole within the hole, to the point at which plenitude and emptiness touch one another."

Most of the works featured in this exhibition relate to one or more of these interpretations of openings. In addition, they all share a preoccupation with architectural spaces, and are either set within buildings or make use of domestic windows and doors. At the same time, sexual, psychological, or religious themes are addressed in these works in a subtle, almost imperceptible manner. Some of the works touch upon the Renaissance preoccupation with perspective, which at times has a religious, specifically Christian, resonance. Others are concerned with the creation of novel architectural structures, which in some instances include existing ruins or vestiges of destroyed sites. An additional group of works deals with the subject of the desiring gaze and voyeuristic urge related to peering through various openings.

Like the ceiling frescos created by Renaissance painters, Lihi Turgeman'scompositions revolve around various apertures, seducing the eye and luring it into a hole that seems to lead into infinity. Yet, while the light-filled apertures featured in classical church frescoes are filled with light and a promise of redemption, the apertures in Turgeman's work are mesmerizing dark holes that pull the gaze inwards, arresting it and threatening to swallow the viewer. Shiri Doron creates paintings and collages on small wooden cubes, combining architectural and artistic images cut out of tourist postcards of Florence with oil paintings of domestic thresholds. In some instances, the composition includes several openings that echo one another; in others, the cutout images include phallic symbols or male figures facing various openings, which constitute obvious sexual allusions.

Ania Krupiakov's work In Search for Anna is based on images of different European churches. These images are assembled together to create a single architectural space composed of flat, transparent colonnades that create an illusion of depth. In this manner, Krupiakov attempts to structure an almost painterly perspective, flattening the image into a fine-line drawing and reconstructing it as a three-dimensional installation.

The use of apertures as openings to alternative worlds, or imaginary architectural structures, recurs in a number of the works included in this exhibition. Ilit Azulai's works feature imaginary sites built on vestiges and memories. She uses images taken from books about vanished places, combining them with small objects and metal parts she collects in construction sites or in ruins of demolished houses. These objects are subsequently placed in the studio and photographed in a manner that creates a play of perspectives between the different elements, forming an architecture of openings and passageways. The titles of her works – such as Lobby,Bridge, and Passage – are imbued with a sense of mystery that draws the gaze inwards, in an impossible attempt to peer through the window, beyond the column or though the door, and to uncover the site's invisible aspects. Sharon Paz'svideo work The Door keeper is similarly concerned with destruction and construction, and with the creation of an opening into another world. This work features a male figure walking among urban ruins (a hybrid image composed of images of Berlin and ones photographed during the Second War in Lebanon), while carrying a door on its shoulders. This marker of a vanished threshold, perhaps the last vestige of a destroyed home, also represents the possibility of rebuilding life elsewhere, and the search for a safe haven in the midst of destruction. Inspired by the world of molecular biology, Nivi Alroy is similarly concerned with survival in a disrupted habitat. The title of her work, Fruiting Bodies, makes reference to a biological state of distress in which cells compete for nourishment and light by climbing one on top of the other, in an attempt increase their chances of survival. In this work, an untamed architectural organism erupts out of a chest of drawers, spilling its hidden contents out into the light. The fact that this spiral structure represents a symbiotic relationship, in which two life forms are dependent on one another for their survival while simultaneously destroying one another, may also allude to Israel's political reality.

An additional group of works examines openings from a voyeuristic perspective, often inviting us to peer through a hole while simultaneously obstructing our gaze. Yiftach Belsky photographs his unsuspecting neighbors through his apartment window, while Efrat Vital follows the neighborhood hairdresser with her camera. Her lens captures its subject through the slats of a shutter, and the view is occasionally blocked in part by passing pedestrians or cars. And even though at times the hairdresser appears to be aware of the camera's presence and to return the photographer's gaze, the photographer remains in the position of a voyeur, while the only eyes truly met by the lens are those of the image painted on the salon's window.

The scenes painted by Eyal Sasson, which are based on images from museums of natural history, capture the intersecting gazes of visitors, museum ushers, animal skeletons and exotic animals imprisoned within glass dioramas; paradoxically, the gazes cast by the silent exhibits seem more direct and alive than those cast by the visitors. Lihi Chen places a door at the center of the gallery, creating an unexpected physical and visual disruption. A careful gaze detects the hints of a potential disaster within the illusory domestic space that lies beyond it. Indeed, when one peers through the eyelet, one discovers a lamp that has gone up in flames, setting the entire room on fire. The act of peering through the eyelet, and the location of the burning lamp within the installation, calls to mind Marcel Duchamp's last work Étant donnés, which Itamar Levi defines as "a work that is all hole." As Levi describes Duchamp's work, "The viewer peers through a hole in a wooden door, which opens onto a brick wall. The wall itself contains a fissure that opens up onto an illuminated space, where a naked woman lies on a bed of twigs, her bent legs pulled lightly apart, her genitals exposed, while one of her hands holds a lamp…" Indeed, this work by Duchamp seems to be located at the intersection of the psychological, voyeuristic, sexual and perspectival discourses on holes in the history of art, while serving as a point of departure for different readings of the group of works featured in this exhibition.

Ravit Harari