Hothouse | חממה 22/03/2012 - 30/04/2012

Hothouse, a Collaborative Project by Tal Frank & Keren Anavy

The inspiration for Hothouse, our joint project, is the hothouse as both a visual and metaphorical image, as a locus and breeding ground designed to rule nature and organize it. In our exhibition, the hothouse is expropriated from its original use, while the gallery space is made into an arena of research whose derivative objects are cultured and managed only in appearance. The starting point for our project was the ecological greenhouse established by artist Avital Geva in Kibbutz Ein Shemer in 1977, together with Rafi Shapira.* The eco- greenhouse at Ein Shemer, which remains active to this day, is an innovative learning environment for environmental studies, art and further disciplines, and serves as an experimental site for social and artistic research.

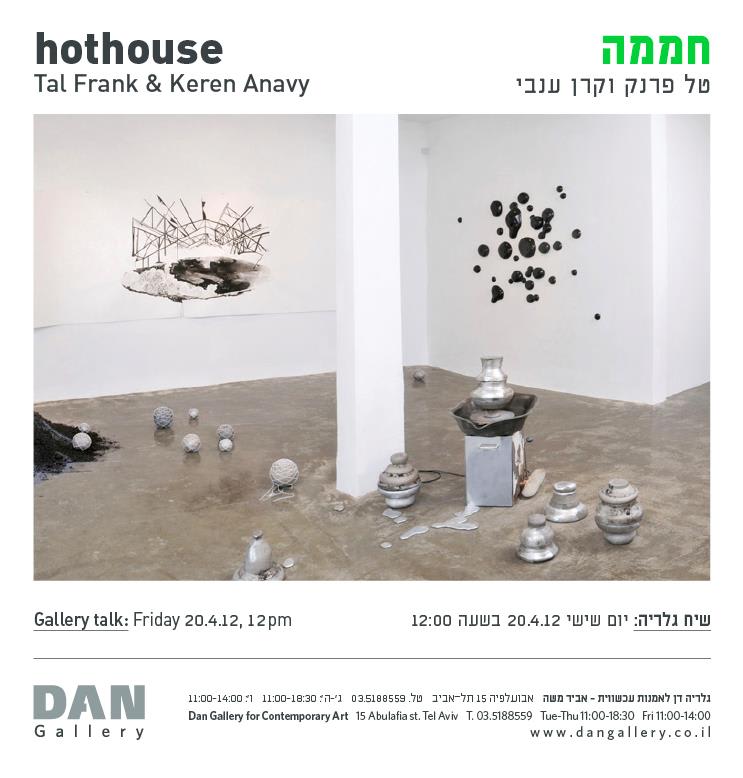

In our project we have constructed a kind of fictive breeding ground for gems and artifacts – such as diamonds, which are a recurrent theme in our work. But while hothouses are normally designed to regulate nature and manage the cultivation of its products, our art hothouse yields forms and objects that break the fundamental pact with nature – objects that, in terms of their materiality and treatment, tread the thin line between control and the loss of it: The black ink drawings that hang on the walls outline an arena of confrontation in which ink is to be tamed and mastered, despite its essential fluidity; and the various sculptural objects scattered on the floor, which at first sight seem as ceramic vessels made at the potter’s wheel, are in fact aluminum casts devoid of any utility, and are suggestive of production and industry.

Our use of the ink drawing technique, along with that of metal casting, introduces a dimension of play between the governed and incidental, the contingent and planned, and between attempting to discipline matter, to rule it and camouflage it as another – and ultimately succumbing to it. We aspire to offer the viewer an experience that conveys a longing for a new order of things, a different, alternative framework where the beautiful is confronted with the ugly. This experience finds its expression in finely-made artifacts, even as they maintain a degree of deliberate roughness. The monochrome that

dominates the exhibition, whether in the stylized minimal ink strokes or in the excess ‘chatter’ the hothouse generates, brings about an equivocal system where beauty is mixed with morbid overtones. The hothouse depicted in the drawings is therefore something of a floating, unfounded utopia, which indeed seems to lack any hold on the ground in any of the drawings. It appears rather as a complex, laden site, as a surreal sphere of an ever straying reality, or as a novel framework where form and content are cast into shape.

The works on display reference geometric and architectural structures on several levels: The hothouse structure in the ink drawings, with its inclined roof and geometric water basins, also echoes the diamond-like structures it houses – emblems of wealth and felicity, which also represent an unattainable ideal of flawless order and symmetry. In contrast, the sculptural, ceramic- seeming objects evoke cinerary urns or stupa monuments – Buddhist burial shrines, their mound-like domes growing pointed spikes that carry phallic significances, but are also symbolic of death. Despite first appearing as containers or as objects rooted in traditional pottery, they are in fact completely sealed and therefore without any use value – but rather the vegetal mutations that have sprouted in the fictive hothouse. These are containers unable to contain, decorative items that fail to embellish their surrounding space.

The new ecological order proposed here is a seductive and enchanting one, where diamonds glitter and decorative vessels grow – an order that generates new concepts of beauty. But it is also a disrupted ecological order, whose objects of beauty posit an illusion abound with contradictions: The mock ceramic urns, made of cast aluminum, were produced using sand molds which lent them the somewhat faded, ragged aspect of archeological finds dug-up from the ground – as surviving relics of an ancient-futuristic civilization. Only partially polished, they appear at times shiny and at times coarse; beside them are heavy iron balls evocative of led weights or old cannon balls – aggressive objects suggestive of a masculine world of warfare and industry, despite their feminine ‘diamond’ embellishments; and this while the ink drawings, which leap into the gallery space, break the conventional

rules of display. The choice of paper, as a support for the array of images they carry, is designed to offer an alternative route within the actual exhibition space.

The main themes tackled in the show are those that preoccupy us in our individual artistic practice. We are concerned with notions of beauty and with the creative process, one that is motivated by the ‘cultivation’ and generation of ideas and things of beauty, as well as the role or error and coincidence within this process. In our sculptural wall piece, which consists of a cluster of oversized ink splatters that appear to have been carelessly splashed on the wall, it is this allegedly accidental ‘error’ that seems to have generated this new form of beauty. This ‘error’ takes its place within a carefully constructed work of art, where each such stain was meticulously hand-made and hung on the wall according to a carefully devised pattern. Our hothouse, as a site of both alchemy and trial and error, enables us to bring about these fruitful contradictions, with which we may question and challenge the accepted notions of beauty in the art world.

Tal Frank and Keren Anavy

*A Kibbutz is a communal form of settlement unique to the Zionist movement in Israel. It is founded on socialist values, equality and the sharing of economic and resources and ideas between its members.