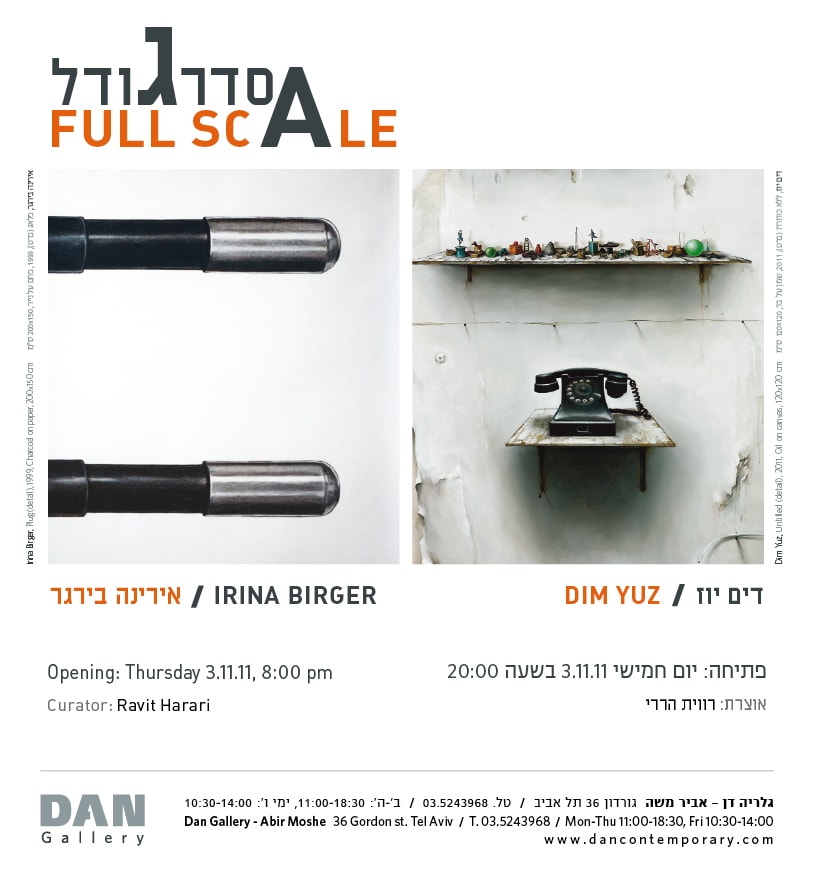

Full Scale | סדר גודל 03/11/2011 - 16/12/2011

The exhibition Full Scale features works by Dim Yuz and Irina Birger – two artists who received a traditional art education in the former Soviet Union and later immigrated to Israel. Although their works differ from one another in terms of their subject matter and style, they are similarly characterized by a meticulous process of execution and by a concern with quotidian, domestic objects, whose scale and materiality are radically transformed in order to produce an imaginary, emotionally charged sphere.

Dim Yuz's works are concerned with representations of memory. Yuz frequently represents environments in which he lived in the past, or attempts to capture the memory of living in them. He paints or creates cardboard sculptures of domestic spaces and personal objects, which come together in his works to form a puzzle composed of personal and universal memories. His realist oil paintings capture spaces that appear neglected or abandoned, while his sculptures – which are made of an ephemeral material, constitute an analogy to the elusive materiality of memory itself. In this manner, Yuz creates a language based on the relationship between fragments of memory and the possibility of embodying them in the present.

The background in Yuz's paintings is always the same dilapidated old wall, whose peeling paint seems to represent layers of memory or different temporal registers. The patches of peeled paint resemble an abstract geographic map of an unknown country, while the composition itself appears to extend beyond the painterly frame. In most of the paintings, series of blurred numbers are imprinted on the cracked walls. These are the numbers imprinted on the shipping containers carrying the belongings of immigrant families – a numerical code referring to the time and place where the container was packed, to its contents, and to the private memories of each individual family. The inevitable Jewish and Israeli association of these numbers with the Holocaust ties Yuz's paintings to the realm of collective memory, which exceeds that of the artist's personal memories. The shelves stretching along the peeling walls feature rows of miniature toys whose obsolete appearance differs significantly from that of the plastic brand names that currently dominate the toy market. Toy soldiers, wooden horses, colorful blocks, a blue castle, a tricycle, tin airplanes and wooden cars are lined up one alongside another, nostalgically alluding to a past that no longer exists. In some compositions, the figure of a wooden clown wearing a pointed hat and a striped outfit appears at the corner of a shelf. This figure is based on that of "Buratino," a Pinocchio-style Russian cartoon figure popular in the Soviet Union during the artist's childhood. Yet Yuz's clown, a sort of self-portrait in disguise, is not a smiling and upbeat doll like its source of inspiration. It appears limp and lifeless, like an object abandoned or forgotten, its posture attesting to its loneliness and resignation to its fate.

Yuz's paintings are presented alongside his cardboard sculptures of domestic and other objects. Despite the ephemeral quality of the cardboard, Yuz engages in a labor-intensive process to produce elegant, meticulously crafted sculptures that appear to have been created out of an expensive, durable material. The choice of cardboard not only produces an analogy with the elusive materiality of memory, but also leaves much room for the viewer's imagination. This crude, weightless, colorless material carries no textural or cultural charge, and enables viewers to project onto it their own associations. In this manner, the objects are detached from the artist's private realm of memory, and become general representations of memory. In 2006, Yuz participated in the exhibition "Mini Israel" (The Israel Museum, Jerusalem), which was concerned with the role of models. For that exhibition, he created a miniature cardboard caravan identical to the one where he lived with his family during their first years in Israel. In this caravan, which was no larger than a shoebox, Yuz reconstructed every single furniture item and object, creating a perfect, miniscule domestic environment within a small dollhouse. At present, he engages in an inverse strategy – blowing up everyday domestic objects to monumental dimensions: a clothes hanger that is two meter long, a tricycle that could not possibly be used by a child, or clock cogwheels resembling gigantic spinning tops. In this manner, Yuz seems to be gazing into the entrails of time like a child curiously gazing into the entrails of a clock, whose fascination with the cogwheels results in the arrest of the clock's movement. These enlarged objects reconstruct a childhood experience, and cause the viewer himself to feel once again like a child as he faces these sculptures.

Miniature objects blown up to monumental dimensions are similarly at the center of Irina Birger's works. Her series of meticulously executed charcoal drawings on paper ("Object Studies," 1999–2001) revolve around small, almost esoteric everyday objects – such as a pushpin, a camera lens, or part of an electric plug. By enlarging their scale, she removes them from their immediate context and endows them with an iconic presence. Their enlargement also underscores the design and aesthetic value of these simple, quotidian objects, whose qualities usually escape the eye. Birger's concern with the gender roles played by men and women is a recurrent theme in her works (such as the series "Men Collection," in which the artist photographed herself with randomly encountered men in different countries). This interest is similarly pursued in "Object Studies," which touches, among other things, on the relation between the functional role of different objects and their definition as masculine or feminine nouns in different languages, such as Russian and Hebrew. Some of the objects she examines have inherently masculine qualities, like the pushpin designed to penetrate through a sheet of paper; yet in Russian, the noun "pushpin" is a feminine one. The monumental presence of these enlarged objects underscores their symbolic resonance as gigantic phalluses, or as round objects imbued with a feminine quality (such as the camera lens). Birger's drawings, like Yuz's large-scale sculptures, are reminiscent of the gigantic sculptures created by Claes Oldenburg (b. 1929), who produced sculptures of familiar objects on an architectural scale in order to remove them from their familiar surroundings and associations, and transform them into icons commemorating consumer culture. Yet while Oldenberg's works are characterized by a humoristic, lighthearted quality, which characterizes much of Pop art, Birger and Yuz's monochrome works are serious, restrained, and elegant, and are imbued with a nostalgic atmosphere that may be related to the artists' cultural background and experiences of immigration.

Birger's works frequently allude to her early life in the former Soviet Union and to her experience of immigration, while bespeaking a search for a personal artistic language and for a connection to the Western culture in which she lives and works today. In addition to directly addressing these themes in a number of video works (such as Irina Birger Thinks: Drawing is Important, 2010; and Tuning, 2006), her drawings are repeatedly concerned with symmetry and aesthetic values based on a central focal point; such elements produce a sense of power, and appear in popular images in both communist and fascist cultures. The conscious use of these aesthetic features transforms her drawings into spectacles of power, which implicitly relating to the totalitarian culture in which she was raised.

Birger's combination of charcoal drawings on paper and video projections, and of mundane objects and electric devices, creates a fusion of warm and cold, old and new, organic and technological elements. Oftentimes, she combines manual drawings with digital effects and sound works that create a hypnotizing, dream-like effect. Equalizer (2011), for instance, is a 3D animation work projected onto a drawing of an equalizer (an electronic device for equalizing sound frequencies). The combination of a projection and a drawing produces an optical illusion of a real object that appears to be embedded in the wall, its buttons moving up and down in an imaginary attempt to equalize the sounds emanating from it. This work exemplifies Birger's recurrent engagement with the relations between old and new types of media. Her work Headache (2003) for instance, which was included in the 2006 exhibition "Fata Morgana" at the Haifa Museum of Art, consisted of an animation work projected onto a large-scale charcoal drawing of a turning radio dial. The soundtrack accompanying this work consisted of random transmissions from radio stations broadcasting in different languages, which came together to create the impression of a never-ending journey. In both these works, the combination of a charcoal drawing and a video projection creates the illusion of a concrete object; yet while the dial in Headache appears to be protruding from the wall, the equalizer seems to be engraved into the wall like a scratch or a scar. In either case, the viewer is invited to embark on an emotional journey, vacillating continuously without being able to stop at any one station or to reach a decisive equalizing point. In this manner, these works metaphorically examine the experience of immigration and the sense of foreignness that accompanies life in a new cultural environment: a life characterized by communication difficulties and an attempt to find the right "frequency," as well as by a constant attempt to respond, to find one's equilibrium, and to adjust to a new cultural environment.

Ravit Harari